Some Things I Remember about Frank Moorhouse

News of Frank Moorhouse’s death at 83 — a respectable age at which to check out, I suppose, but it still felt way too soon — struck me harder than I bargained for, the loss of this friend from many years ago.

And the photo in the Wikipedia entry came as a shock. Who was the grandfatherly character in a rumpled shirt and suspenders (suspenders!)? What had happened to the dashing fellow I knew?

That immediately triggered a memory of one of his early pieces in which the main character (him) decides, after an erotic disappointment, to forget managing his waistline and quits doing situps.

Many more memories followed on the heels of this one, and I felt moved to catalog them in more or less chronological order.

1.We met at a literary conference at the East-West Center in Honolulu in the late 70s. A much more famous Australian writer tattled to me that unlike the other participants Frank had paid his own way (a brief glimpse here into the fierce rivalries these fellows engaged in). The fact was, Frank loved conferences. You couldn’t keep him away. He’d written a short piece called “Conferenceville” detailing both the protocol and the many pleasures of these events. One imperative, I recall, was always to pick up every handout you were offered. I don’t remember much else about Frank from this gathering except that he wore a safari jacket and presented an affable persona.

2. We next met in Balmain, Sydney a year or two later, where I was based before traveling to the Great Barrier Reef. Here I got to know Frank better and read some of his early collections of stories, which struck me as utterly fresh and unique in terms of what he was trying to record about his own and his characters’ personal lives. The unabashed truthfulness of the stories made such an impression on me that now it’s hard to separate what he told me from what he recounted on the printed page.

Frank, I was told by others, had been a member of the Sydney Push, which had happened only a few years before but was now, in the late 70s, considered ancient history; I was to remain to this day very much in the dark about what the Push actually was. Already expert in winning arts funding, he had acquired a young intern underwritten by the Australia Council to help him organize his papers and remarked mischievously that he feared, possibly with good reason, the satirical roman a clef that would result. Frank had previously been the target, in those pre-social media days, of some literary pranksters who had assumed his identity for various anarchist purposes.

3. We weren’t lovers, though that prospect had been on the table (and I remember the fish-eyed stare of an Australian editor at the Frankfurt Book Fair when I mentioned I knew Frank). What we were was pals, and that was the better choice. His love life was complicated, and already a source of embarrassment and regret to him even then, I think. He recounted the travails of an endless cycle of taking women out to dine with his credit card and feeling the world’s eyes in judgment on him.

His stories about sexual attraction to other men, seemingly far less of a source of embarrassment, had already appeared when I came to Sydney. Almost overnight, he told me, his friends with children wouldn’t have him over any more. I don’t know what sort of connections he made in the years that followed, but at the time his emotional life seemed tied up almost wholly with women.

It’s fair to say Frank could be difficult. Though always pleasant company in the middle distance of friendship, he could be excruciatingly high strung in more intimate encounters. I was told by others about a friend of theirs, a woman he was involved with, spotting a look of discontent on his face as she was getting off a plane to meet him, causing her to realize in a flash that somehow he had already decided their connection was not going to work. I had a taste of this years later when I told him, after an outing north of the Golden Gate, how I’d organized the day in advance and was then angrily accused of manipulating him.

I am being frank about Frank, because that is exactly what he was, always, in conversation and in writing. It was an unspoken but absolute ethical position that won my total admiration. How many writers (or people generally) would confess to looking at themselves in a group photo and recognizing the expression on their own face as unmistakably obsequious and anxious to please?

4. We shared a love of bushwalking. Frank took me on a camping trip into the bush south of his hometown Nowra, which I heard a lot about. He could remember the “seductive” American GIs roaring through in their jeeps during World War II; they were the first adults he had ever seen chewing gum. We also passed a town with the unlikely name of Happy Valley, which Frank wistfully and unironically declared was in fact a paradise of fulfilled hetero coupling.

Of the walk itself, I remember undistinguished scenery, a pass I wasn’t able to accept, and another of Frank’s random confessions that forever stuck in your mind: a previous bushwalk where he’d been absolutely unable to get the repeating song verse “She’ll be comin’ round the mountain when she comes” out of his head.

5. Frank visited me a few times in the San Francisco Bay Area as he was passing through. Once he thoughtfully brought me a pair of gaiters after he’d heard my story of having my bare legs slashed to ribbons on a tramp with some sadistic Kiwis on New Zealand’s North Island. American hikers don’t wear gaiters as a rule; we either don full-length trousers or shorts, as the terrain requires. When I’d asked if the walk required long or short pants, they’d said shorts and then sneered at my lack of trail savvy when I showed up gaiterless.

On this trip we stopped by Cody’s bookstore on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley so Frank could buy a copy of The G Spot, a sensationalist bestseller of the day, that a friend had asked him to get. It’s typical of Frank that you knew for sure it really was a friend he was buying it for, not himself euphemistically disguised. If he’d been buying it for himself, he would have said so. Though I don’t doubt he read it cover to cover on the plane home.

Frank, I knew, was fond of the beatniks. There was another time when he showed up late one night after a weary set of plane delays and I took him to San Francisco’s North Beach for a drink in one of its famous old bohemian bars, Gino and Carlo’s (not Vesuvio’s, too obvious!). But it wasn’t long before he was forced to admit to utter jet lag fatigue and we left after raising only a single glass to the Beats.

6. We were last in touch a few years back and exchanged books by post (he still had that same box in the central Sydney P.O.!), a very little book of stories from me and a very big novel from him. Cold Light was so different from the raffish tales of his youth that it felt like a different person had written it. It was serious. It was proper, written in an unexceptionably mainstream literary style, with a genteel third person heroine whose face never betrayed the unmistakable signs of recent orgasm that one of his earlier women characters unforgettably did. Where was the outrageous quirky detail? The palpable delight in fearless and unflattering self-exposure? I am ill equipped to pass judgment here, since my reaction was doubtless compounded by a Yank’s distance from the finely calibrated machinations of Canberra politics of a bygone era, a subject Frank might be fairly said to have gotten deep into the weeds with.

7. Finally, one word keeps spinning around in my mind in much the same way as “She’ll be comin’ round the mountain” did so long ago in Frank’s. That word is beloved. Hearing of the outpouring of memories of good deeds, generosity, and kindnesses at his death, I wondered if anyone had yet applied it to Frank. I have a memory — again I can’t tell if it’s something he told me or in a piece of his I read, though I think he told it to me — of Frank bringing up the word in relation to writers. Did he say it had already been used to describe him? Based on what he’d written so far, I doubt it. No, I think there was again that wistfulness in him, that longing, however ironically presented, to be so described, side by side with a belief in the unlikelihood of its ever happening. Beloved was what I believe he wanted to be, in his life and in his writing. What a fine thing, in the years since I knew him, if that has come to pass.

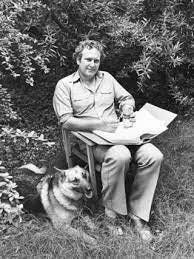

Oh my. The old Frank!